This article originally appeared in the Summer 2023 issue of On The Level.

By Wendy Holliday Bledsoe and the Vestibular Disorders Association

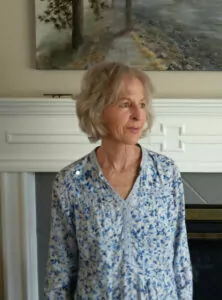

One day in 2016 Melinda woke with a stiff neck. She’d been painting a ceiling the day before and thought that she’d recover quickly as she’d always done before. However, the next day at work she didn’t feel well.

“During a morning meeting I could feel something very odd happen. I could almost hear a whooshing sound,” Melinda says. “My mind and vision had difficulty focusing. When I got up to leave the meeting and I started to move, my surroundings felt like they were spinning.” This episode of vertigo marked the beginning of Melinda’s vestibular disorder journey, which would significantly alter her life.

From Therapist To Patient

Before her condition Melinda worked as an Occupational Therapist. She loved helping people with mental and physical disabilities, injuries, and illnesses regain independence in their daily lives. However, constant bouts of vertigo made her a patient.

Before her condition Melinda worked as an Occupational Therapist. She loved helping people with mental and physical disabilities, injuries, and illnesses regain independence in their daily lives. However, constant bouts of vertigo made her a patient.

As a healthcare professional, Melinda understands what happens when the complex vestibular system becomes disturbed and the havoc of that breakdown on the whole body. “I was trained in vestibular rehab, so I have an interesting perspective. I sit on both sides of the fence in regards to thinking about how therapists treat vestibular disorders, and then on the flip side of having to be the patient of the treatment.”

When the Dizziness Persists

Melinda was diagnosed with BPPV and started the normal treatments. But even after long-term consistent treatment and the help of multiple vestibular experts, the treatments weren’t making her better. That’s when she started to realize that her dizziness might stick around a lot longer than she and her doctors had hoped.

She explains “For the people who end up with a positional vertigo and get treated, and it resolves, that’s just so wonderful. And that is the case for most people. But, as one doctor said, ‘you’re the one-percenter – the small piece of the pie of vertigo patients that it just doesn’t resolve.’”

Anxiety and Depression

Anxiety and Depression

Amid her brain spinning, Melinda didn’t recognize the manifestation of depression until she looked back on her journey. She says, “I had some depression [and anxiety]. I didn’t really recognize it as such: Just this low level of always being on edge about what I have to do that day.” Melinda believes that she’d have fared better if she had been open to the idea of medications to help with anxiety and depression.

Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD)

As Melinda’s condition worsened simple tasks such as bending, lifting, and turning triggered many problems that affected her whole body. Melinda recalls, “Over the first year my vertigo transitioned to dizziness. I felt like my brain was a bowl of water, and I was losing my body boundaries.”

Now, seven years into her vestibular journey, Melinda is dealing with a long-term condition that is called Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD). In addition to recurring dizziness, she is also impacted by difficulty perceiving what she describes as her “position in space.”

Melinda explains “I get a sense of disorientation when I’m in a crowded environment. It’s a very odd sensation. For example, I could be in a meeting sitting down, then when everybody gets up I have to organize and plan how I’m going to do that comfortably without feeling like I’m going to start fumbling, or I’m going to bump into somebody. Because of the other activity happening around me, I lose my sense of boundaries. I have to pay attention to where I am in regards to other people, so I feel a sense of insecurity, like, ‘Am I going to pull this off?’ It’s very complicated. Call it ‘disassociation,’ or ‘where I am in space,’ I am definitely affected by that.

Melinda is not the only person in her family who has experienced these dissociative feelings because of vestibular dysfunction. She has a 6-year-old niece named Francis who has suffered from episodes of vertigo since the age of 2.

Melinda is not the only person in her family who has experienced these dissociative feelings because of vestibular dysfunction. She has a 6-year-old niece named Francis who has suffered from episodes of vertigo since the age of 2.

“We’ve been trying to work with her to give her language for this terrible sensation that she has, and she has started saying things like, ‘I just don’t belong in this world. Sometimes I feel like this is all a dream and we don’t actually exist on the earth.’

When Francis was first told that the earth is always spinning she said “Oh! I think that’s why all the people in the world feel dizzy.”

Melinda explains, “You just know that when she has these vertigo episodes, she’s not grounded. She doesn’t feel her body tied to the earth. And I think that’s what our vestibular systems do. They impact how we deal with gravity, and they play such a big part in making us feel like we’re supposed to be on the earth. Our feet are grounded. We’re moving in space. We’re negotiating people around us. Our sense of depth and perception is not accurate. So, I think that disassociation is very real. We probably all experience it in slightly different ways, but she phrased it well.”

You Don’t Look Sick!

As disabling as these feelings are, they can’t be seen from the outside. Aside from the occasional stumble and stagger that an outsider may perceive as clumsiness, few can grasp the mental and physical struggles and challenges a vestibular sufferer experiences daily. Melinda sums it up best when she said, “In regards to their response to me, whether it be friends, coworkers, even my husband, because it’s a hidden disability, they forget about it. And they forget that certain things are creating a level of stress for me.”

These days, Melinda avoids bringing her illness up with her friends and family members. “I get tired of saying the same thing. Yeah, it’s there. It’s with me all the time, every day, every night. And it’s not that they don’t believe me, but they don’t understand. Unless you’ve had vertigo and you can say, ‘Oh god, yeah, I know what that feels like,’ people often just say ‘Oh, you know, that’s too bad.’ And I can’t expect more than that, right? Because you can only relate to what you can relate to.’

Moving Forward

Melinda counts her vestibular malfunction as one of those big things in life that redefines her sense of self.

Melinda counts her vestibular malfunction as one of those big things in life that redefines her sense of self.

She let go of her career as an Occupational Therapist to focus on healing. Given time and retraining, Melinda understands the brain’s ability to heal itself. “For me, I know that I just have to keep pushing the envelope. Brains want to change, but they won’t change unless you are challenging it.”

She has rediscovered her love for oil painting and writing. And, as an avid hiker Melinda returned to walking using a walking stick. Melinda says the walking aid “provides another point of proprioceptive feedback for my brain to use when trying to determine where my body is in space.” And when she needs help, the simplest and most personal form of support is nearby. “Sometimes, I need to just hold hands with my husband.”

Finding Hope

Melinda felt alone in her dizziness and was thrilled to connect with others and learn more about her condition through VeDA. “When I discovered VeDA, that was huge.” She says, “You just don’t know what it’s like until you’ve had to experience it. Actually hearing stories of people who’ve had vestibular issues for years… I used to feel like something had to be really wrong with me because it was hanging on for so long. But the different stories and research on VeDA’s website really helped me hone in on what’s going on with me.”

“I would like to convey to people in the throws of long term vestibular disorders to keep hope because there is still joy to be had, you just need to dig a little deeper to find it.”