Watch MUSC: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

Have you or a friend experienced what you thought was a recurrance of BPPV, only to find out it was not BPPV causing your symptoms? Here we present a case study to help illustrate the difference between BPPV from other vestibular disorders.

Case Study

Ann had been successfully diagnosed and treated for BPPV by a vestibular-trained physical therapist last year. She remained free of vertigo for several months. Then one morning she woke up feeling very dizzy again. Her symptoms continued for a couple of days, including nausea, vertigo, and light-headedness. The first day Ann found she needed to hang onto walls and furniture to be able to make it to the bathroom.

By the third- or fourth-day Ann felt better and was able to return to work. However, the dizziness had not fully resolved. She no longer felt like she was spinning but did have a dizzy sensation off and on through-out the day.

She made an appointment with the vestibular therapist that she had seen previously, thinking the BPPV had returned. The vestibular therapist evaluated her and determined that it was not BPPV that was causing her symptoms, so they sent her to follow up with her doctor for further medical assessment.

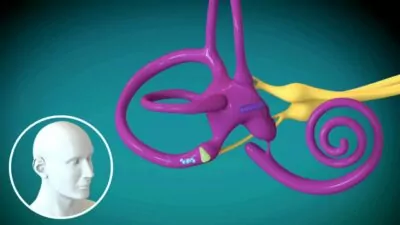

Ann visited her ENT (Ear, Nose and Throat doctor), who, after running some tests and evaluating her medical history, diagnosed her with “unilateral vestibular hypofunction” (i.e., significant loss of function in one of her inner ears). He speculated that this might have been caused by an inner ear infection, otherwise known as “vestibular neuronitis.” If caught early, Ann’s condition could have been treated with antibiotics or steroids, but since the onset of her symptoms was over a month ago, this treatment would not have been effective. Instead, he recommended that Ann return to her physical therapist for vestibular rehabilitation therapy. Like BPPV, vestibular hypofunction is very treatable but does take longer to respond to treatment.

Unlike with BPPV, which presents with spinning vertigo, Ann’s symptoms now were more of a light- headed sensation. Ann’s therapist noted that moving Ann’s head, especially, quickly made her symptoms worse. They instructed Ann to walk for 50 feet with her head still, and then with her head moving. Ann was really surprised that moving her head markedly worsened her symptoms. The therapist performed a thorough evaluation, looking at Ann’s eye movements, vision, and balance.

The therapist explained that unilateral vestibular hypofunction is a condition where one of the two vestibular organs is no longer functioning at 100%. This results in a mismatch between the signals being sent to the brain from the right and left vestibular systems when the head is moved, causing a lightheaded or dizzy sensation. She also reassured Ann that although it is not as quick a fix as BPPV often is, the condition responds well to vestibular therapy. Exercises performed consistently can train the brain to adapt to the mismatch between the vestibular organs, and as this occurs the dizziness gradually gets better and eventually resolves.

Ann was given an exercise program for training her vestibular system. This included “habituation exercises” for training her brain to better process head and body movement as well as “adaptation exercises” to train the head and eyes to coordinate while moving around in the world. She was also given exercises for improving her balance. At first the exercises made her dizzy, but the therapist helped her figure out how to calibrate her program so the dizziness was tolerable and quickly resolved after each exercise session. Over time, as the exercises became easier, they were made more challenging. Ann worked on these exercises daily at home as well as in therapy sessions, as consistency and repetition are important to recovery.

As the exercises became easier Ann noticed she was feeling better. Her dizziness was occurring less often, and when she did notice it, it was less severe. She felt safe to return to driving. She could now go to the grocery store for short periods of time, though she still held onto the grocery cart for security.

Eventually, Ann was able to resume all her usual activities. She no longer needed to do her vestibular exercises, but continued with the balance work to help decrease her fall risk as she continues to get older, which is a good idea for anyone!

Below is a general summary of the difference between BPPV and unilateral vestibular hypofunction.

BPPV |

Vestibular Hypofunction |

Symptoms |

Symptoms |

| Spinning sensation with changing position | Dizzy, lightheaded sensation with quick head movements |

| Symptoms last a few seconds to a minute and stay resolved until changing positon again | Symptoms occur off and on throughout the day. Often it is related to activities requiring head movements, though this is not always obvious at first. |

| Walking and moving the head, such as while grocery shopping does not bring on symptoms | Walking and moving the head when shopping, looking over the shoulder, turning a corner, frequently bring on symptoms |

| Tipping the head back to look up such as to reach into an upper shelf brings on symptoms of spinning or vertigo | Tipping the head back may bring on transient light headedness but not an episode of spinning |

Treatment |

Treatment |

| Type: Canalith repositioning maneuver such as the “Epley maneuver”

Duration: often 1-2 visits. In complex cases of BPPV in both ears or in more than one semi-circular canal, more treatments may be needed. |

Type: Exercises designed to train the vestibular system and brain to adapt to changes in function.

Duration: usually 2-3 times a week for 4-6 weeks, though in some cases need a longer duration. |

Additional Resources:

By Camille Tingle, PT, DPT, author of Dizziness and Vertigo, Causes and Treatments