Your first step in recovery is to get an accurate diagnosis.

Ten years ago I experienced a profound bout of dizziness, disequilibrium, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms after taking the anti-malarial drug mefloquine (previously marketed as Lariam) prescribed to me by the U.S. Navy at the start of the Iraq war. I took the drug weekly for five months.

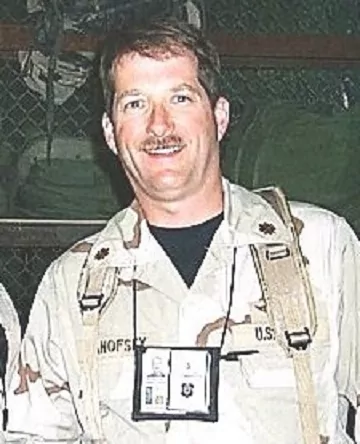

Prior to taking mefloquine, I had been in excellent physical and mental health. I was flight rated with a top secret security clearance, and had deployed to the Iraq war to support special operations.

Several months after starting the drug, I looked like I had Parkinson’s disease. I had continuous tremors in my arms and hands, and I stuttered when I talked. I had such acute photophobia that I had to wear two pairs of sunglasses just to go outdoors during the day.

As I struggled with my symptoms after returning home from the war, I sought additional diagnosis and treatment outside the Navy. The kind volunteers at Mefloquine Action USA (a support group for those suffering the adverse effects of the drug) referred me to Dr. Owen Black, an otolaryngologist. After extensive testing, Dr. Black diagnosed me with a permanent vestibular injury. Dr. Black prescribed me a cane to walk with, and began extensive vestibular therapy. I was also evaluated by Dr. Panelope Suter, a neurooptometrist, who diagnosed me with a central convergence disorder and prescribed me vision therapy.

My symptoms were so unusual that some Navy doctors accused me of malingering. Fortunately, an experienced Navy otolaryngologist, Dr. Michael Hoffer, recognized my condition and attributed my vestibular symptoms to mefloquine. The mefloquine package insert warned of a risk of vertigo and other neuropsychiatric symptoms with the drug, but implied that the symptoms would be temporary. But by this point, I had been suffering the effects for months without improvement.

With Dr. Black’s and Suter’s earlier workups supporting the diagnosis of Dr. Michael Hoffer, I was able to convince the Navy of the full extent and cause of my injury. The Navy initiated a full medical board leading to my retirement, acknowledging that I had experienced a lasting reaction to mefloquine. To my knowledge, I am the first veteran ever discharged with a diagnosis of mefloquine-induced vestibular disorder and the first to receive a disability rating from the VA for its effects.

For the past ten years, I have been reaching out to other veterans who have experienced similar reactions to the drug. I have personally assisted over one hundred and thirty service members and veterans seek proper medical attention for their symptoms of mefloquine toxicity. I have also assisted the VA in establishing a clinical intake program at the War Related Illnesses and Injuries Study Center in New Jersey for veterans who have taken mefloquine. Slowly, veterans are coming forward, recognizing that some of their chronic neuropsychiatric symptoms – anxiety, mood and cognitive problems – dizziness, disequilibrium, and sleep problems, might be due to mefloquine. Indeed, a recent publication by the Centers for Disease Control concedes that the neuropsychiatric effects of mefloquine may confound the diagnosis and management of posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.

I support the continuing work of Johns Hopkins researcher Dr. Remington Nevin, who is the country’s leading expert on the effects of mefloquine. Dr. Nevin’s research has uncovered studies in the literature revealing the class of drugs to which mefloquine belongs, the so-called quinolines, have been known for over 70 years to cause mutifocal neurotoxic lesions to vestibuloocular nuclei and other brainstem and brain centers. Mefloquine has also recently been shown to be neurotoxic to scattered nuclei in the brainstem. Dr. Nevin believes that a toxic brain and brainstem injury is responsible both for the chronic vertigo and visual symptoms, and the cognitive and mood problems that I and possibly thousands of other mefloquine-exposed veterans suffer from. In a 2012 case report, Dr. Nevin diagnosed a young U.S. Navy sailor who had experienced symptoms very similar to my own with a toxic limbic encephalopathy and central vestibulopathy.

To this day I still experience significant symptoms of vestibuloocular injury. I cannot walk heel to toe. When I stand up and close my eyes, I fall over. I am ever cautious as to how I orient my head since I have recurring violent vertigo episodes. I am very sensitive to bright or flickering lights. Dr. Suter recently measured my convergence disorder and commented that my eyes still do not look at the same words when I read. I participate in speech therapy at the VA and receive intermittent visual and vestibular therapy. Although my symptoms have improved somewhat over the previous decade, I am still troubled daily by symptoms.

Last year, the FDA Commissioner’s office contacted me requesting a meeting to discuss concerns with the safety of the drug. I assembled a team including Dr. Nevin and several mefloquine victims who presented testimony to the FDA this past February. FDA has recently placed mefloquine on a safety watch list for concerns of vestibular disorder and is currently performing a full review, which will hopefully lead to a significant labeling changes later this year that will better inform physicians and patients like me of the drug’s potentially toxic and permanent effects, and lead to much needed research into the diagnosis and treatment of this condition.