There is no way another person can identify with the far reaching visceral and surreal experience of vestibular dysfunction unless they themselves have dealt with vertigo.

I was an Occupational Therapist working in pediatrics for thirty plus years. When I was 57 in 2016 my life changed. I had been painting a ceiling for several hours with short intermittent breaks to rest my neck. The next day I awoke with a very stiff neck, but proceeded to work as usual. During a morning meeting I could feel something very odd happen. I could almost hear a whooshing sound. My mind and vision had difficulty focusing. When I got up to leave the meeting and I started to move, my surroundings felt like they were spinning. This continued day after day. My vertigo never reached a debilitating level, but was enough to wreak havoc on my ability to carry out my job and other tasks smoothly. Oddly enough, I had recently signed up for a course in vestibular rehabilitation for PT’s and OT’s. They used me as the assessment guinea pig and it was clear that I had BPPV of the right posterior canal. However, the Epley maneuvers did not work for me, and unfortunately aggravated my upper cervical neck pain. I found myself challenged to walk down the school halls with children walking past me, the bright lights, and turning corners. I felt like my brain was a bowl of water, and I was losing my body boundaries, often referred to as the “position in space”.

Within a year I was evaluated at the Vestibular Clinic at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, with a resulting diagnosis of Posterior Canal BPPV. I also had a brain MRI to rule out central nervous system problems. I received vestibular PT, which included Epley maneuvers, as well as other maneuvers, as my diagnostic symptoms (eye nystagmus) were subtle and not entirely clear as they had been in the beginning. I made some progress, though minimal, and was advised to keep up the exercises.

Over the first year my vertigo transitioned to dizziness. The triggers were certain head movements and complex visual stimulation, i.e crowded places, narrow isles, and transitioning from walking to upward elevations/downslope or approaching curves on a path. Thankfully, driving was not hugely impacted. A little more than two years into this I went for another full vestibular assessment, this time at the University of Washington Vestibular Clinic. The diagnosis was undetermined right side BPPV, which meant that it was a positional vertigo but they did not know what canal was the problem, and again recommended doing those things that made me dizzy.

I am now seven years out. Approximately three years into my vertigo/dizziness I did need to leave my job. The visual stimulation of working in a school environment with all the unpredictable turning with resulting dizziness was simply too exhausting, along with the unresolved neck pain that increased with head flexion. I believe now I would fall into what is labeled PPPD.

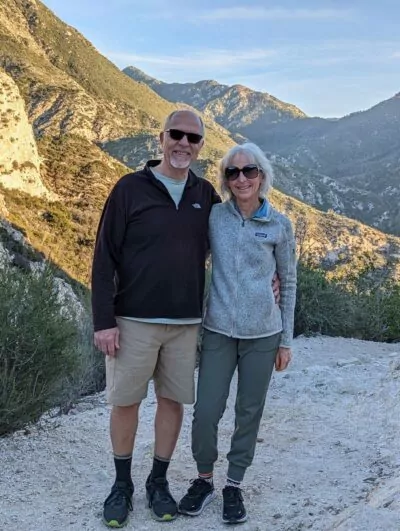

About six months after leaving my job I applied for Social Security Disability and was granted it. I took several years off to try to find my balance and rest. I picked up my oil painting and found great peace with that. I definitely experienced mild depression in those early years as I was determined to keep up with the activities I had previously done, such as walking, hiking, jogging, and biking. All of those activities now took a certain amount of concentration concerning depth perception, and dealing with the dizziness and lack of groundedness. It took a piece of the enjoyment out of what previously was performed seamlessly.

Today I continue with all the same issues, but I recognize the incremental progress that has happened so slowly that it has taken conscious effort to document that I have indeed made progress. I can now tolerate going into a busy store, and though I still get dizzy episodes and occasionally feel like I am losing my position in space, it is nowhere near what I used to experience. I can walk down a busy sidewalk without feeling I am going to end up in tears. I continue to have mild depth perception challenges. But for me, I realize when I am hiking over rough terrain, that my perception is better than it feels to be. I tire by the afternoon and generally feel dizzier, so I try to pace my activities and accept my limitations. I have found a part-time new career in real estate. This allows me to work one on one with people and generally within controlled environments. As a past Occupational Therapist I understand the complexity of the vestibular system and the amazing connections it has to the rest of the brain’s functions. I see the subtle but real effects of my vestibular dysfunction in my cognitive performance. The main issue I see is my sequencing skills. This plays out when I am writing or typing, frequently typing letters out of sequence or writing numbers, like an address, out of order. This issue also affects my organizational skills. When presented with a multitask I find myself feeling momentarily confused and having to take more time to sequence the tasks. It can be with something as simple as wanting to gather several things up at once and experience a short glitch on how best to tackle it. I also notice my binocular vision is minutely off, and fine motor skills are mildly affected, depending on the day. I continue to do visual and balance exercises almost daily, even though at times they feel worthless. But what I do notice is, if I don’t do them it is just a matter of time before the symptoms worsen.

I have found supports and techniques that help reduce the uncomfortableness of the vestibular dysfunction experience. Such as, when I am walking, I consciously feel my feet hitting the ground versus feeling my head floating. Using a walking stick provides another point of proprioceptive feedback for my brain to use when trying to determine where my body is in space. I always double check my writing and love spell check. I give myself grace when fine motor or multitasking, especially with objects, feels clumsy.

In summary, I would like to say that vestibular dysfunction is a journey. Most likely it will improve over time because the brain does want healing and balance restored, but it is a huge task for it to learn to ignore or adapt to misinformation coming from the inner ear, no matter what the cause. This is where all the exercises are important. We need to give it as much opportunity to challenge itself and learn what it has to do to function as normally as possible in a busy gravity driven world. It is important to remember that physical balance is a three prong event. The brain takes information from the muscles and joints, vision and vestibular system to keep us upright and moving successfully. When the vestibular system is not giving accurate information, the brain will try to rely more on the proprioceptive system (feedback from joints and muscles) and the visual system as the more reliable sources. That is why visual exercises, balance activities, and movement in general is critical to keep sharp. The last point I would like to make as a past therapist working with people with vestibular dysfunction is I can honestly say, there is no way another person can identify with the far reaching visceral and surreal experience of vestibular dysfunction unless they themselves have dealt with vertigo. We hardly even know how to explain it ourselves, and this is where support groups are hugely helpful, and I hope they continue to pop-up in every community.