PLANNING FOR TRAVEL WITH A VESTIBULAR DISORDER

Planning a trip while managing a vestibular condition requires a bit of extra preparation, especially if it is your first trip post diagnosis. Here are a few questions to ask yourself while planning your trip:

- What types of travel increase my symptoms?

- What can I do to minimize discomfort while traveling?

- Is my destination friendly to my sensitivities?

- What do I need to talk to my doctor about?

Asking yourself these questions and reflecting on the answers can help you prepare for your journey. Other issues you may want to consider include:

- Weather patterns

- Planned activities at your destination

- What to bring to manage your symptoms

- Communicating with your travel companions in advance about your needs

Does my Diagnosis Prevent Me from Certain Types of Travel?

Having a vestibular disorder does not have to prevent you from traveling. However, some types of travel may be more appropriate than others. Traveling with a vestibular disorder that is impacted by pressure in the inner ear and its fluid (Perilymph Fistula, secondary endolymphatic hydrops, and Meniere’s Disease) can cause symptoms to arise when there are pressure fluctuations during travel, such as flying on an airplane.

by pressure in the inner ear and its fluid (Perilymph Fistula, secondary endolymphatic hydrops, and Meniere’s Disease) can cause symptoms to arise when there are pressure fluctuations during travel, such as flying on an airplane.

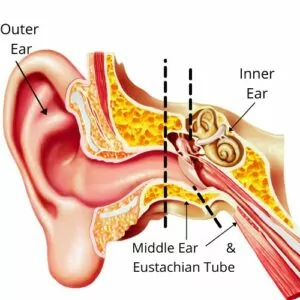

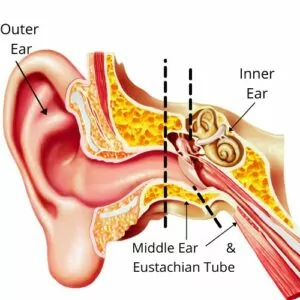

According to the Association for Research in Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, ear problems are the most common medical complaint of air travelers. This is largely because changes in altitude and fluctuating pressure impact the middle ear, which is the pressure regulation portion of the ear. The ear ‘pops’ when one changes elevation in order to change the pressure and volume of air in the space between your eustachian tube and ear drum. For most people, this is temporary and popping your ear allows for air to flow through the eustachian tube, equalizing the pressure in your middle ear so it matches the pressure outside of your body. This change in pressure helps to keep your eardrum intact and maintains equal pressure in your inner ear. For most, this is just a mild irritation, but for those with vestibular disorders, this change in pressure can trigger other symptoms.

Vestibular disorders with symptoms caused by pressure fluctuations may flare up during rapid ascents and descents or in other elevation changing situations. Volume and pressure are inversely proportional – both gas (air) and fluid (endolymph and perilymph fluids in your inner ear) react to changing altitudes. There is a constant change of pressure in your inner ear as you travel up and down in elevation, whether you’re on land, in the ocean, or in the air. This relationship can be thrown off and cause dizziness or vertigo in those with pressure-related vestibular disorders. Take special care with or avoid unpressurized air travel, underwater diving, and fast elevators.

Here are a few tips to avoid rapid elevation and pressure changes:

- If staying in a high-rise hotel, ask for a room on the first few floors.

- Avoid ‘hopper’ planes (smaller planes that typically go short distances).

- Find out ahead of time if your train or car ride will have large mountain passes with major elevation changes.

- Avoid scuba diving, freediving, and swimming in deep water.

- Chew gum, yawn, sip water frequently, or use another way to pop your ears, especially during descents.

- Ask your doctor if you can take a decongestant. This can help keep your nasal passages clear, which helps with pressure equalization.

It’s important to note that those who are post-operative from Semicircular Canal Dehiscence repair surgery should not fly for a specified amount of time. This decision should be made by your surgeon.

Additionally, those with a perilymph fistula should ask their healthcare team about if it is safe for them to travel, and about the precautions they should take if plane travel is necessary.

Planning Around the Weather

Barometric pressure changes happen with changes in heat, humidity, storms, and other weather events. Often people with vestibular disorders report they can ‘feel a storm coming,’ as if it’s a sixth sense. While you cannot change or control the weather, you can sometimes choose a travel destination to avoid weather patterns associated with pressure changes, such as tropical storms.

Changes in atmospheric pressure can affect those with Meniere’s Disease, secondary endolymphatic hydrops, and vestibular migraine (1,2). There is not much research stating why or how this may happen. For those with Meniere’s Disease (1), however, one study found that increased pressure was problematic. For those with vestibular migraine low pressure systems were more problematic (2).

For more information on weather and vestibular disorders, click here.

Here are some tips to find places with fewer barometric pressure changes.

- Accuweather has a migraine tracking feature. To find this feature:

- Go to Google.com

- Type in “Accuweather migraine forecast (+ your desired city)”

- Search and then click the top Accuweather result

- Research places that have few weather and barometric pressure changes to vacation when possible.

- Pack your “rescue kit” to help you if a weather event should arise.

Packing for Your Trip

Besides clothes, shoes, and toiletries, pack all the items you use to manage your symptoms on a daily basis, as well as anything you might need in an emergency. Your “rescue kit” may include a water bottle, medications, light-sensitivity glasses, hat with a brim, heating pad, and more (see below).

Medications

Always keep your medications and supplements with you. Whether they’re for prevention or used to abort or rescue an attack, medications should be by your side at all times. Be sure that you have what you need in your carry-on baggage, not your checked luggage.

It is not recommended to change your medication routine when you travel. If time differences are a factor, ask your doctor what’s best for you when changing time zones. You may need to take the medication or supplement at a new time so that your body keeps on the same schedule, or you may be able to take it at another time.

Food and Water

Always pack a water bottle! It’s important to stay hydrated. Water and/or water containers are not always easily accessible. A small to medium, lightweight water bottle is best..

If your vestibular symptoms are triggered by food, bring your own snacks. Packs of safe seeds, crackers, and power bars are often great options to throw in your backpack or purse to make sure you have something on hand in case you need it. This is especially important during the days you’re traveling. Airports and train stations are notoriously unpredictable, and they do not always have safe food options.

Here are some resources that may help you plan your travel diet:

Pantry Staples (and Snacks) for those on a migraine diet

Check out the list of foods from the VeDA dietary considerations list!

Accessories

Sun/light-sensitivity glasses, anti-nausea bands, ear plugs, a hat, a foldable cane, and other useful items may be on your list. Whether you are on a plane, in a bright environment, or somewhere with an uneven surface, these tools can come in handy to keep your trigger-load low. The key is to think through all the situations you may be in to predict what you may need.

TRAVELING TO YOUR DESTINATION AND THROUGHOUT YOUR TRIP

Getting there

If you have the time it is recommended to budget a day on either end of your trip to get acclimated to your new environment. Often people with vestibular disorders are triggered by travel, so your first day should be low-key and restful. This does not mean that you have to just sit in your hotel room for a full day, but if you’re planning on having one day to lay by the pool, go to the spa, or otherwise relax, making it the first day may help you acclimate before adventuring.

Motion Sensitivity

Vestibular disorders cause altered processing of motion cues. When the signals aren’t firing accurately, this creates motion sickness (car-sickness or sea-sickness). Here are a few tips to help you manage motion sickness and the accompanying nausea:

- If you’re on a car trip, and you can safely drive, ask to be the driver rather than the passenger so your body knows when acceleration and deceleration are going to happen. This will help your body adjust to the motion more easily.

- If you are the passenger on any form of transportation, make sure you can see outside when choosing your seat. Focus on the horizon because this helps stabilize your vestibular system.

- If possible, get out and walk around frequently to help decrease the length of time you are in passive motion. Take breaks at rest stops or when the train is in the station. You could also schedule a layover when flying.

- In passenger trains with seating on two levels, sit on the lower level where there is less sway (rocking motion).

- Avoid reading, using your phone/computer, and other activities that require your head to be down throughout your journey.

- Ask your doctor about a vestibular suppressant or other medication you can use during your journey.

- Pack a rescue kit with items to help nausea if it arises (see below).

Those with Mal de Debarquement Syndrome may feel better during passive motion and worse when the motion stops. This can also occur if a person has developed movement and postural compensation strategies in response to a chronic vestibular disorder. If passive motion helps you to feel better, you may enjoy the ride, but prepare yourself instead for when you get off the transportation.

- Bring a cane if you have trouble balancing after you deboard.

- You may need some time to rest after getting off the boat/train/plane/etc.

- Talk a short walk after you get off of your vehicle and focus on the horizon.

Visual Vertigo & Visual Sensitivity

Vestibular dysfunction often increases our reliance on the visual system for balance. Because your visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems should work together to help you balance, when one has a dysfunction the other two need to work harder to compensate. For people with a vestibular disorder, this typically results in visual dependence, which can cause visual vertigo and visual motion sensitivity.

Airports, train stations, parking lots, and traffic are incredibly visually stimulating environments. When paired with travel-fatigue, they can be even more irritating to your system. Here are a few tricks you can use to help minimize these symptoms:

- Wear sunglasses or other tinted glasses to decrease irritating lights and patterns.

- Rest your eyes when you can.

- Wear a hat to decrease the amount of light and irritants in your peripheral view.

- Talk to your physical therapist about what you can do to prepare for being in visually stimulating environments.

Nausea & Vomiting3

Motion sickness and visual vertigo can cause nausea and/or vomiting to occur during your trip.

- Ginger is your best friend! Ginger can help reduce nausea and comes in many forms, such as chews, candies, and teas.

- Practice deep breathing – inhaling and exhaling deeply and slowly will help decrease nausea, especially if you can be outside or roll down a window for fresh air.

- Peppermint or lavender oil can help reduce your nausea response – apply it on your temples or diffuse it into the air.

- Peppermint gum, tea, or candies can also reduce nausea.

- Seltzer or sparkling water can settle the stomach.

If motion or visual sickness causes vomiting, it’s important to stay hydrated and try to keep something in your stomach, if possible.

- Drink fluids slowly, approximately 1-2 oz every 10-15 minutes.

- Eat only well-tolerated foods.

- Bland foods, such as crackers, potatoes, rice, and noodles, can be helpful.

- Avoid milk products for 24-48 hours.

- Avoid fried or greasy foods.

- Bring an emesis bag in case you need it.

- Talk to your provider about an antiemetic medication if this is a frequent symptom.

OTHER STRATEGIES

- If you have a balance problem and are traveling to an unfamiliar place, pack items that will help you manage uncomfortable light and sound disturbances. These might include sunglasses, a hat with a visor, a flashlight, and ear plugs.

- Standing in long lines and walking through airport terminals or train stations can be tiring for a person with a balance disorder because these large, open, echo-filled spaces are disorienting. In this circumstance, you might find it helpful to use a cane or hold onto the extended handle of a suitcase.

- Some automobiles have curved windshields that have distortion at the lower corners. This is merely annoying for most persons, but it is often disorienting for those with visual sensitivities. If your travel plans include renting a car, prior to signing the rental agreement ask to sit in the front seat of the proposed vehicle so you can test the comfort of the windshield’s optics.

- Try to arrive in the evening so you can walk around to calm your system down a little bit, then head right to bed to reset for the morning.

Although traveling, and planning to travel, with a vestibular disorder may feel daunting at first, adequate preparation and planning can help ease your nerves so you feel more prepared, resulting in a more enjoyable experience.

By the Vestibular Disorders Association with edits by Madison Oak, PT, DPT

by pressure in the inner ear and its fluid (Perilymph Fistula, secondary endolymphatic hydrops, and Meniere’s Disease) can cause symptoms to arise when there are pressure fluctuations during travel, such as flying on an airplane.

by pressure in the inner ear and its fluid (Perilymph Fistula, secondary endolymphatic hydrops, and Meniere’s Disease) can cause symptoms to arise when there are pressure fluctuations during travel, such as flying on an airplane.  NO MORE GLARE

NO MORE GLARE